Introduction

The Covid-19 Pandemic started as an outbreak in Wuhan, China in December 2019. It spread quickly and was declared a pandemic on 11th March 2020 by WHO. As of 16th April 2020, the virus has infected 2.1 million individuals in 210 countries and claimed over 140,000 lives. Statistics show recovery in 573,000 people; the possibility of reinfection or relapse cannot be ruled out even in recovered individuals.

There is wide variation between countries in the levels of transmission between people, susceptibility within individuals to infection, and morbidity/ mortality rates. In addition, geographical variations exist in the availability and preparedness of medical facilities to deal with the pandemic. This necessitates a country or region-specific approach in the initiation of containment and treatment measures. Since Covid-19 is a predominantly respiratory illness, it places a differential burden on various subspecialties of medicine. Equally, all health care workers (HCW) are expected to offer their services in a pandemic situation to fight the disease to their capacities.

Covid-19 occurs in its most serious forms in the elderly and in individuals with pre-existing medical conditions; children being relatively spared the worst effects of the illness [1]. However, the highly invasive nature of orthopaedic surgery places HCW at high risk of acquiring the illness when operating on patients with Covid-19. Paediatric Orthopaedics is firmly in the middle of these two counterbalancing factors. Specific evidence-based guidelines for Paediatric Orthopaedics will be difficult to formulate at this time. Therefore, existing guidelines are, at best, extrapolations that will help the clinician make informed choices about patient care.

The majority of children with Covid-19 develop a sub-clinical or mild illness and are vectors, likely to be important in transmission of the disease. Reducing the number of outpatient visits and shortening the duration of clinical contact with children is therefore essential during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Singapore was one of the first countries to receive a Covid-19 patient from China. Having experience of dealing with the SARS Epidemic in 2003, the Singapore government had a framework in place for a timely and effective response to Covid-19. The Singapore experience of Covid-19 has been summarised in a well-written document and a perusal of the same is recommended [2]. Briefly, the Singapore approach was guided by 3 principles which we would all do well to bear in mind during decision making.

- Clinical urgency

- Patient and HCW protection

- Conservation of health resources

Salient changes in orthopaedic practice at Singapore hospitals during Covid-19 include:

- Prioritisation of all operative cases based on clinical urgency. Patients requiring urgent or early orthopaedic care were managed in the usual way. This included all trauma and tumour surgery. Day surgeries such as soft tissue releases, arthroscopies and metalwork removals were allowed to continue.

- Elective, non-urgent procedures requiring > 23 hours of hospitalisation were postponed.

- Restricting outpatient visits and screening of outpatients using history of contact/ travel and temperature measurement.

- Segregation of outpatient and inpatient clinical care teams to protect doctors from infecting each other.

- Avoiding surgery in immunocompromised individuals and those with co-morbidities.

- Use of full PPE during surgery including PAPR (powered air purifying respirators)

- Reducing operating time to the minimum, minimising the scale of the intervention if possible and restricting movement of HCW in the operating theatre.

- Routine good hygiene practices, social distancing and taking individual responsibility for health.

Whilst this question would appear to be fairly straightforward and common-sensical under normal circumstances, there is widespread difference in the interpretation of this term during pandemic times. Guidelines issued by various subspecialty orthopaedic groups do not concur in their estimation of harm that would potentially occur if a surgery was deferred or delayed [3].

The surgeon should therefore exercise sound judgement and abundant caution whilst deciding to operate on a child. Parents/ legal guardians should provide written informed consent after fully understanding the potential harm vs. benefit of the procedure including the risk of acquiring nosocomial Covid-19 infection. No data exist at present to quantify the risk of operating on a child during a pandemic. A second opinion from a senior colleague(s) may be obtained in doubtful cases.

Guidelines for surgical prioritisation were issued on 11th April 2020 by the four surgical Royal Colleges with NHS England, offering the first specific guidance for paediatric orthopaedic conditions [4].

Patients requiring surgery during the COVID-19 crisis have been classified as follows

| Priority Level | Classification | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Emergency | Operation needed within 24 hours |

| 1b | Urgent | Operation needed within 72 hours |

| 2 | Surgery that can be deferred for up to 4 weeks | |

| 3 | Surgery that can be delayed for up to 3 months | |

| 4 | Surgery that can be delayed more than 3 months |

The guideline lists specific paediatric orthopaedic conditions according to Priority Level:

| 1a (24 hours) | 1b (72 hours) | 2 (1 month) | 3 (3 months) | 4 (> 3 months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Septic arthritis | SCFE | MDT directed aggressive benign bone tumour | DDH (Primary joint stabilisation) | DDH (Secondary joint reconstruction) |

| Osteomyelitis | MDT directed malignant bone/ soft tissue tumours | Mensical repair | CTEV (initial management including tenotomies) | CTEV (Late presenting or relapse) |

| Fractures: Open/ NV or skin compromise | Displaced intra-articular/ peri- articular fractures/ Forearm and femoral fractures | Limb length equalisation/ deformities (time bound physeodesis) | Spasticity management (CP operative management in general) | |

| Dislocated joints | Exposed metalwork | Corrective surgery for established deformity) | ||

| Compartment syndrome | Reconstruction for established joint instability (ACL, lateral collateral ligament) | |||

| Metalwork removal |

The guideline acknowledges that the time intervals suggested above “may result in a higher risk of an adverse outcome due to progression or worsening of the clinical condition”. Maintenance of a database of all patients awaiting surgery will help to keep track of cases. Weekly updates from parents through video consultation will help to reprioritise surgical timing in case there is a change in the clinical condition.

British Orthopaedic Association and Orthopaedic Trauma Society also issued guidance on the management of musculoskeletal injuries in children during the Covid-19 pandemic [5]. The relevant section is reproduced below Background

During the coronavirus pandemic, there will be increased emphasis on managing children with non-operative strategies and minimising outpatient visits. The aim is to minimise long-term consequences by prioritising conditions that have immediate, permanent morbidity or lack a practical remedial option.

Principles of outpatient management during Covid-19 pandemic:

- Always consider the possibility of non-accidental injury. The principles of management are unchanged.

- If necessary, children with the following suspected diagnoses may be managed without radiology at presentation:

- Soft tissue injuries.

- Wrist, forearm, clavicle and proximal humeral fractures.

- Long bone fractures with clinical deformity.

- Foot fractures without significant clinical deformity and swelling.

- The following injuries may be managed without a cast at presentation:

- Knee ligament and patellar injuries may be managed with bracing.

- Stable ankle fractures may be managed with a fixed ankle boot or Soft cast.

- Hindfoot, midfoot and forefoot injuries may be managed with a fixed ankle boot or plaster shoe.

- A single follow-up appointment at 4 to 12 weeks, depending on the limb or bone fractured, is acceptable for the majority of injuries.

- Patient-initiated follow-up is appropriate for the following conditions:

- Patellar subluxations and dislocations, knee ligament and meniscal injuries, excluding locked knees.

- Lateral malleolar fractures and suspected ankle avulsion fractures.

- Foot injuries, except suspected mid- and hindfoot injuries.

- Wrist, forearm, clavicle and humeral fractures, including proximal humerus.

- Gartland type 1 and 2 supracondylar fractures.

Non-operative management

- Many children's injuries may be definitively managed in a cast at presentation. Wherever possible, use reinforced Softcast for home removal:

- Extra-articular tibial fractures without neurovascular or soft tissue compromise.

A small number of these patients may require intervention: - Admit if high risk of compartment syndrome (adolescent or high energy injuries).

- Consider sedation for reduction of clinically important deformity.

- Accept that residual deformity or malunion may require corrective surgery.

- Displaced wrist fractures in children aged under ten years.

- Undisplaced ankle and forearm fractures.

- Gartland types 1 and 2 supracondylar fractures.

Operative management:

Suitable for Day-Case Surgery

- Most children who require operative management may have surgery as a day-case:

- Reduced joint dislocations.

- Fractures with abnormal neurology or soft tissue compromise that is resolving after treatment.

- Peri-articular fractures.

- Extra-articular femoral fractures in children aged under six years (spica cast).

- Displaced forearm fractures.

Management of obligatory inpatients

- A small number of patients require inpatient treatment with anaesthesia and operative management:

- Open fractures (consider wash out with windowed cast).

- Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis with subperiosteal collection.

- Femoral fractures in children aged over six years (operative stabilisation).

- Displaced articular or peri-articular fractures, including Gartland type 3 supracondylar fractures and

- Acute slipped upper femoral epiphysis.

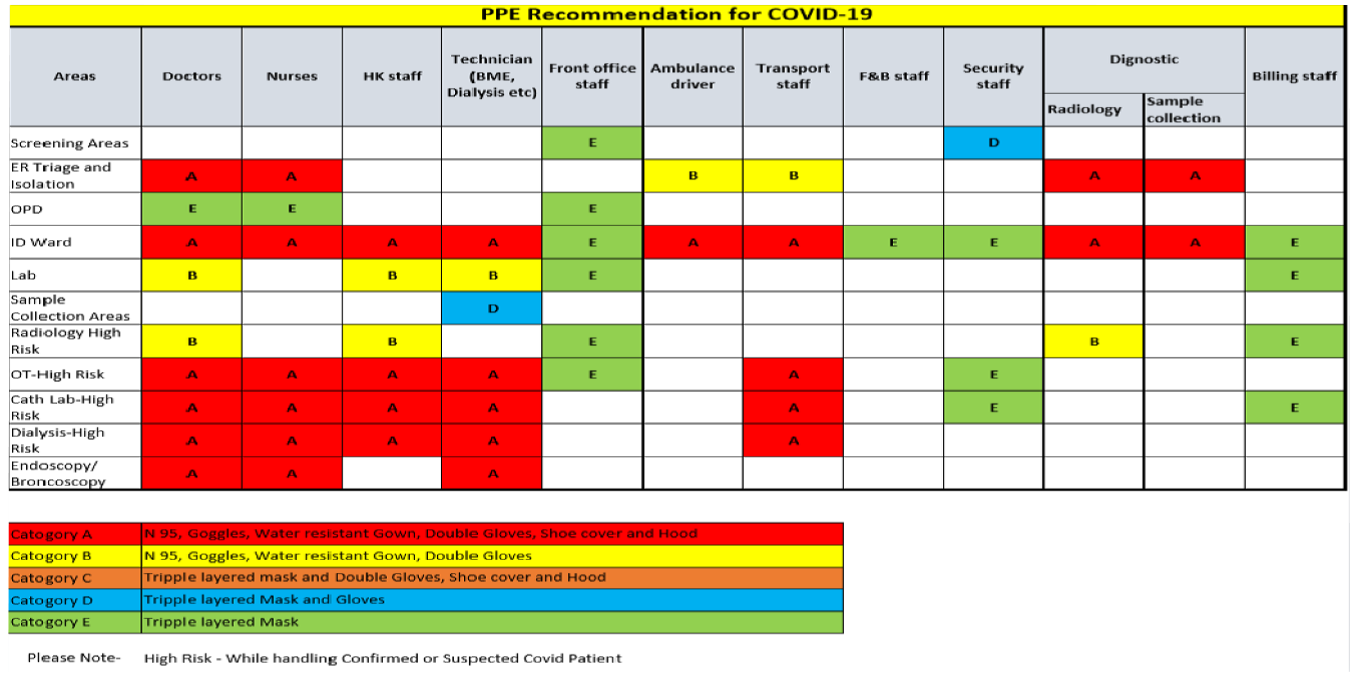

There is a shortage of PPE all over the world. PPE kits add to total cost of healthcare and it makes sense to rationalise their use. The following is a ready reckoner regarding rational use of PPE kits [6].

| Setting | Target ersonnel or atients | Activity | Type of PPE or rocedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare facilities | |||

| Inpatient facilities | |||

| Patient room | Healthcare workers | Providing direct care to COVID-19 patients. Aerosol-generating procedures performed on COVID-19 patients. |

Medical mask, Gown, Gloves, Eye protection (goggles or face shield). Respirator N95 or FFP2 standard, or equivalent. Gown, Gloves, Eye protection, Apron |

| Outpatient facilities | |||

| Consultation room | Healthcare workers | Physical examination of patient with respiratory symptoms. Physical examination of patients without respiratory symptoms. |

Medical mask Gown, Gloves, Eye protection PPE according to standard precautions and risk assessment. |

| Consultation room | Patients with respiratory symptoms. Patients without respiratory symptoms. |

Any | Provide medical mask if tolerated. No PPE required |

| Consultation room | Cleaners | After and between consultations with patients with respiratory symptoms. | Medical mask Gown, Heavy duty gloves, Eye protection (if risk of splash from organic material or chemicals). Boots or closed work shoes |

References and further reading:

- Tagarro A, Elpalza C, Santos M et al. Screening and severity of Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) in Madrid, Spain. JAMA Paediatrics. Published online April 8, 2020.

- Liang Z C, Wang W, Murphy D et al. Novel Coronavirus and Orthopaedic Surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2020; e1 (1-5).

- DePhillipo NN, Larson CM, O’Neill OR et al. Guidelines for ambulatory surgery centres for the care of surgically necessary/time-sensitive orthopaedic cases during the Covid-19 Pandemic. J Bone Joint Surg [Internet].

- Accessed on April 17th from here Click Here >>

- For the latest guidelines on how to manage the OT set-up including laminar air-flow, read the latest guidelines from the NHS here. Click Here >>

- A complete guide to the use of PPE by the WHO is available here. Click Here >>

- The latest guidelines for Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery from NHS England can be found here. Click Here >>

- Specialty guides from NHS England for all disciplines in medicine can be found here.Click Here >>

- A video on what PPE to wear in different areas of the hospital is available on YouTube (from AIIMS, New Delhi): Click Here >>

- A short video on the different masks FFP1 to FFP3, N95 etc is available here Click Here >>